Peregudov the Wolf Hunter

By Igor Severgin

Last winter we were travelling through Altai. It was morning. There was not a soul around. The road was empty. All was quiet. No bird chirped and no branch stirred. Only the sound of the wheels gritting against the icy tarmac could be heard.

We travelled in silence.

By the time we reached Gromotukha Pass the day had brightened. Nikolai, the driver picked up speed, pulled out another cigarette and suddenly froze.

– Look, wolves! – He said, peering into the distance.

– Where? – I asked in disbelief.

– There! Straight ahead.

I squinted near-sightedly: wolves they were, running slowly to the left of the road in each others tracks. Hearing the noise of the engine, they hesitated for a second, and then carried on unperturbed. Four wolves.

After about a minute we caught up with them. Our GAZelle slowly crawled along the road, and one hundred and fifty meters from the curb the pack moved silently across the snowy crust.

– Damn! They know no fear! – Said Nicholas indignantly.

He made a long signal with the horn. The head of the pack turned, glancing indifferently in the direction of the car.

"If old man Peregudov was here they would" – I thought, following the wolves with my eyes. Nikolai reached for his lighter and lit up.

I first heard about Peregudov the wolf hunter, 'volchatnik', a couple of years ago from Alexander Zateev, director of the Katun Biosphere Reserve. I do not remember how we started talking about him. I think Alexander was telling me something about the habits of wolves, and then remembered the famous hunter.

– Kuzma Mitrofanych knows all about them here. Once he had an unlicensed shotgun confiscated. It was his only one. So he caught a live wolf in the forest with his bare hands and dragged it to the police station. Take it away, he says, I have brought you in another criminal. They gave him back his shotgun instantly. Pop in and see the old man. You won't regret it.

I remembered the story about the shotgun but it is only now that I finally managed to visit the wolf hunter. Once again, travelling through Altai, I persuaded the photographer Andrei Gilbert to drive to Talda, where Peregudov lives to this day.

The photographer did not take much convincing. Towards the end of February Gilbert had spent an entire month hanging around the Sayan Mountains trying to shoot film of wolf mating rituals (for wolves February is their mating moon). Yet despite the tremendous long-focus lens, the advice of local rangers and a hell of lot of patience, he did not spot anything more than traces of the grey predators left on gnawed ibex. The same lot befell the hunters from Germany, who came in search of trophy skins. But the Germans never needed their shotguns. It was as if the wolves had vanished into thin air. So Andrei Gilbert had his own questions about the 'grey'.

We found Peregudov's house relatively quickly. We whizzed through Talda to the school, talked to a few passers by, made a left turn, passed several homesteads and with that we had arrived. Outside the wooden house, which was darkened from time but still standing firm a clean 'inomarka' was parked, “a Toyota Sprinter” said Andrei thoughtfully and after a short pause. We realised that we were both thinking the same thing: what is it doing here?

An elderly gentleman with a limp in a shaggy Altai hat came out to meet us.

In Talda Peregudov is well-liked by all, but they are wary of him also. He does not suffer fools gladly, neither among wolves nor humans. Once a lynx accidentally fell into one of Kuzma Mitrofanych's traps. (The old man says that his entire life he had mostly hunted wolves.) And close by there lived a man who hunted these wild cats in Peregudov's area. He stumbled upon the trap and could not help himself from taking another man's prey. The 'volchatnik' did not make a song and dance about it. He simply hounded down in one winter all the lynx in the entire area. Nineteen of them.

With that he let it go.

For it was not losing the lynx fur he was worried about. It was the insult that got the better of him. The wolf hunter says that in the Peregudov line no-one ever hankered after what did not belong to them. The very thought of it was a sin.

There had been no hunters in his line before. His ancestors might have set a few live traps but were otherwise renowned for their bee keeping. Kuzma Mitrofanych had spent his entire life in the mountains of the taiga and only now had changed to bee-keeping. People come to him from Moscow for honey and his fellow villagers pop in from time to time to borrow a few bob. About one hundred thousand of borrowed Peregudov roubles are currently walking around Talda village.

But as they say, however well you feed the wolf, he still looks to the woods. The old man seems to live well enough but he is still drawn to the taiga. The wolf work will not let him go.

– I killed my first wolf when I came back from the front. And I carried on after that. There were so many wolves after the war - terrible. They attacked horses and cows and sheep. But the people were starving – Peregudov recalls – Wolves know no limit. If the farmer is not nearby it will tear a whole flock to pieces. He can not bear to leave anything alive. Once he's out running it has to catch something. So we shot the wolves.

– And who taught you to hunt them?

– The wolves, who else? How they live, I lived with them.

I prowled the forest for sixty years and I remember everything, where they go, how they howl ... I was nine when they trusted me with my first gun. It was a 16-caliber "Berdan". So, when I went to the front they took me on as a sniper.

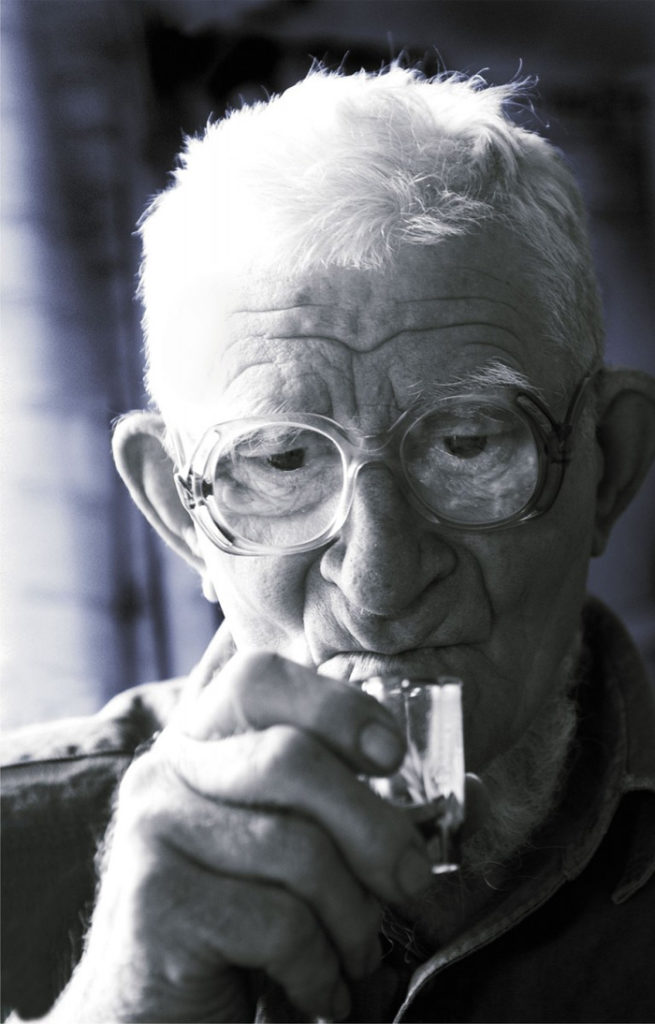

Kuzma Mitrofanych was right about the wolves. You cannot hide a stamp like that. I noticed when we were standing at the gate that there was something of an old wolf about him. He might not have the same strength as before, his glasses have thick lenses and his hair is white as snow, but his eyes are sharp and attentive. When we went into the house I saw a photograph of the hunter holding a live wolf, and I finally understood. With eyes like that you could catch a crocodile with your bare hands, not just a wolf.

The wolves had no chance up against Peregudov. Well, almost none. Once the hunter tracked a pack of eight wolves and killed them all. It is not that easy to get a shot at a wolf. Hunters say that you will never get a clean shot at more than fifty paces. Any more and you will miss. And sometimes it is difficult to get a shot at all it is such a shrewd beast.

– There are not any real hunters left. A day was never enough for me. Even at minus twenty I would tie up my horse in the woods, light a fire and spend the night there – says Kuzma Mitrofanych. – And now what? The wolves are practically walking through the village, and no-one catches them. If I was hunting now I would get fifty in a winter.

– Are not you sorry for the greys?

– Sorry? No. The wolf is of no use to man. I remember thinking in my childhood that it would be better if they did not exist at all. It is better for a sheep or deer to be left for man than for a wolf to have it, and eat it. You see? We were starving then. In 1937 we were eating ground squirrel and vultures whilst the wolves trampled the cattle. Who takes what....

Peregudov may have old scores to settle with the wolves but he has his rules too. He hunts with a shotgun, sets traps and nooses but he will not use poison. Call that hunting? The curious thing is that the wolves probably think the same. The 'volchatnik' told us of a strange case that took place a while ago whilst fishing on the Katun River.

– It was a clear day and the fish were biting well. We lived right on the bank, and slept under the sky. We lay like this, – For some reason Kuzma Mitrofanych demonstrated the position of the body with his outstretched arms. – Then once we got up and what the hell? In the sand right next to where we had been laying were wolf tracks.

They came from downwind. Three of them. They sniffed us but did not touch us. They moved on. They came passed right here, a metre and a half from our feet. If they had attacked us they would have killed us all.

– So they spared you?

– I do not know. Usually the wolf is a merciless beast. Once I saw with my own eyes how they tore apart a stranger. The whole pack attacked, chewed him up and then left. It was right by the fence of the deer farm. But they did not finish the job. He lay there for a bit, crawled another ten meters and then disappeared.

– What do you mean he disappeared?

– His number was up.

Although he no longer hunts as a living, old man Peregudov still goes out from time to time. Last year he and his nephew killed six wolves. Many hunters would envy such a catch but Kuzma Mitrofanych grumbles. He caught more than that even in the worst year ever. True, he cannot say exactly how many wolf trophies he has caught in his lifetime. He was not counting. But in sixty years it must be quite a few.

– Can you pick up the smell of a wolf in the forest? I ask the hunter.

– I do not smell them, but there have been times when my body has made predictions, as if someone was hinting to me where the wolves were.

The savvy nature of Siberia's wolves has gone down in legend. Old man Peregudov told me how once a large pack wandered into their mountains. Eight to ten of them. Sheep, cows, they almost took the lot. Then the men got together, like: "let's get those wolves." Eight days they tracked them but they could not kill them. On the ninth day the wolves tore all the horses apart in a single night, when they were tied up.

– What the hell was that! – says Kuzzma Mitrofanych. – The men got scared and turned back.

All the wolf hunters in Siberia agree that recently the number of wolves has multiplied massively and that in cunning the wolf has no equal.

A wolf can tell a hunter from a simple traveller at a single glance. They stay away from human footprints, but expand their hunting grounds by using cleared strips and sight lines in forests.

Wolves learn quickly. They say that sometimes a pack will pick out a herd of wild boars which it begins to “shepherd”. They kill one animal at a time, just as extra feed. And in the Omsk region the grey predators learned the trick of driving deer onto an old bridge, where the rotten boards caved in under their hooves. With broken legs the deer became easy prey. The most hardened wolves are even unafraid of helicopter hunters. They huddle close to the trunks of trees, and if they are surrounded by steppe, they stand on their hind legs and freeze which makes them almost impossible to spot.

– A wolf can smell danger a mile off. It is a beast as sharp as a button! – says Kuzma Mitrofanych, when we complain to him of the Sayan wolves who so kept their distance from Gilbert. – Now they have taken to living on the deer farms. They dig under the fence and they are in. And what of it? It is a great place! Meat on legs right under their noses. No hunters. They lie low in the nature reserves too. No-one will touch them there.

– They say the red wolf has migrated here from Kazakhstan? Are they really so nimble that they can jump over a deer farm fence two-metres high?

– Rubbish… – snarls Peregrudov authoritatively.

Kuzma Mitrofanych has hunted his entire life even during the war. In forty-one their battalion was sent into the forests of Karelia. Sending them off was one thing but they forgot to deliver the soldiers food supplies. In winter the frosts are fierce leaving nothing to eat. Sniper Peregudov was forced to hunt Karelian deer. He never got used to it and his hands suffered from frostbite, but he saved his battalion from starvation. Together with his partner he shot twenty-eight deer.

Then they were transferred to the Siberian Brigade at Moscow, then Stalingrad. At Stalingrad the war came to an end for the Altai hunter.

– The Germans found me at a site covered in mortar. I lost a leg. They cut my foot off. That is how it happened. The feet feed the wolves and I got a prosthesis, chuckles the hunter.

– So how did life treat you after that?

– Ups and downs. My wife was also a hunter. She hunted squirrels in Ulagan. She loved the taiga so much you could not keep her at home. She would even cry. There were times when she and I would go sixty kilometres on foot. And she caught no less than I did. And her temperament...

– Did you argue?

– You cannot avoid it. Life is never easy. Once I drove the woman out at gunpoint. They gave me six years. I did the whole sentence for a domestic drama.

– Did you really intend to shoot her?

– If I had wanted to shoot her, I would have.

– What happened after that?

– When I got out and we started to live together again until she died. She was bitten by an infected tick.

I did not think at the time to ask Kuzma Mitrofanych to find us a photograph of his wife in the stack of family documents. First I changed the subject and then I simply forgot. Now I regret not having done so. It would have been interesting to see an image of the woman who had been able to catch this “trophy” as at that time Peregudov was well-known throughout the entire okruga. The nature of the wolf hunter continues to surprise. The rangers told us that it was totally impossible to out-drink him. They had tried many times but always failed. Even young healthy men hit their limit towards nightfall, while he just keeps going.

– I'm ready, any time of day or night. Got my shotgun, got my cartridge case, got a trap. That's it – says Peregoudov. - It is just my eyesight that lets me down. Cataracts in both eyes. Had an operation.

– Whose is the foreign car at the gate?

– I know whose, it is mine. I bought it when I turned eighty. Had it driven down here from Novosibirsk.

– How do you manage to drive it?

– How? I get out of the car, feel the road with my hands and then get back in and drive for a bit.

Seeing our surprised faces, the old man smiles slyly. And we realise he is joking.

They say wolves smile sometimes too.

Wolves have their own mating etiquette. During the mating season a lone female wolf howls invitingly, but does not respond to the call of the male. She does not go to meet him. This is the courting period. But when the predators are part of a big pack, the female wolves will forget about etiquette and fight their rivals, sometimes to the death.

– You won't see a wolf here in February. They go to the smooth snows, to the glaciers. They do not drink, eat or even howl for a whole week. They just mate and mate (although Kuzma Mitrofanych put it more directly). It is their wolf wedding. There is no hunting in the taiga that week. I wait until they come down from the mountain snows.

– And when is the best time to hunt a wolf, at night or during the day?

– We go at night. I howl and then, if the wolves come, we shoot them.

– What do you mean you howl? – I ask surprised.

– Quite simply. Wolf-like.

I looked suspiciously at Peregudov. Might he be t ng us again?

– Does it work?

The old man did not answer. He filled his chest up with air and let out a howl.

For a second I did not feel anything particularly except embarrassment. Imagine it, three guys sitting at a table, a bottle of vodka, and one of them begins to howl. But then a light chill ran up my spine. At the time I assumed it was just a one off. But when I arrived back in Novosibirsk I listened to the dictaphone recording and it had exactly the same effect. The wolf hunter's howl was chilling, spine-chilling!

When the howl had ended Kuzma Mitrofanych took a breath, we drank, and he continued:

– In the forest the wolf is master. I have never seen another beast kill a wolf. Only man. Even dead the birds will not touch it. A golden eagle will eat a fox but it will not peck at a wolf's carrion. It is a hard core beast.

– Do you only howl at night?

– Wolves rarely respond to a howl in daytime. So you can only lure them in the evening when twilight has fallen, during the night or early morning whilst it is still dark. Then they will tell you everything: who is wandering alone, and who is being tracked by dogs and where the lair is hidden. During the day I check the traps. I set them on old trails.

– Traps and nooses?

– Yup. In open spaces I mask the traps. If it's on an open field. In the forest I leave nooses where the narrow paths run. If a wolf has killed something it will always return on the third day for its prey. There's another secret. If there is no sound of ravens beside the carrion, the wolf will be too wary to approach. But if the ravens are cawing, you can expect guests. I have brought many wolves back alive in my time.

– What for?

– Just out of interest I took them alive.

– Have you ever tried to catch a bear with a noose? – I ask jokingly.

I've tried, – replied Peregudov. – I was a fool. I thought, I will catch a bear, put my felt boots on my hands to stop it biting me, bind its muzzle and paws and bring it back to the village alive. For a laugh. Then I watched the bear tearing through the noose and changed my mind.

We spent the whole day talking to Kuzma Mitrofanych until eventually it was time to leave.

To round up Peregudov told us how you could tell the age of the hardened predators by their teeth, how to remove the scent from traps and how to get a wolf out of a noose.

– As soon as I see that a wolf is caught in a trap I whittle a stick about two metres long and make for the wolf. You have to be quick! He can get free at any moment. You wave the stick in front of its snout and he quickly nashs it with his fangs. Then I turn the stick sharply landing the wolf on its back. Then I grab the wolf by the ears and clamp its head between my legs. I hold it with one hand and with the other shove a peg between its teeth and wind a rope around its muzzle.

– Between the legs? But what if it bit something off? – perked up Andrei Gilbert.

– You don't hang around!…– the old man grinned.

We laughed, bought some of his honey and made for the gate. Once outside I asked him one final question:

– Kuzma Mitrofanych, you did not keep count of the wolves but when you were a sniper during the war, did you keep count then?

– I did not keep count of the fascists either. How can you keep count when you are wondering whether you are going to live or not?! I do not even know how many bears I have killed. Maybe ten. Maybe fifteen.

We said goodbye and left. I watched the gradually shrinking figure of the hunter and thought to myself: I wonder what the wolves would say about him. But we would never be able to ask them. Of those who knew him, none had survived to tell the tale.

According to popular belief, wolves live with the 'leshiy', the forest spirits. As legend has it, the forest spirit itself can turn into a white wolf. Previously, to appease the forest spirit a shepherd would leave a sheep to be eaten by the grey predators. But there were other "means" of protecting the livestock from wolves such as placing a piece of iron in the stove, stabbing a knife into the threshold or covering a stone with a pot. According to superstitious belief, seeing a wolf on one's journey and having a wolf cross one's path is a sign of good luck. A large number of wolves however foreshadows war.

P.S. The profession of the “Wolf Hunter” has all but disappeared. At least in Siberia the number of remaining 'volchatniks' can be counted on the fingers of one hand. In contrast, the number of predators is growing exponentially and has long been counted in tens of thousands. In 2007 in Buryatia alone more than 200 horses and about the same number of cows were killed by predators. The damage was estimated as amounting to approximately 11 million roubles.

They say that wolves will not attack humans but there are a few "ifs." If the wolf is not starving hungry, if it is not infected with rabies, and if it is not a cross with a stray dog. Wolf-dog hybrids are particularly dangerous. In the Krasnoyarsk region a wolf pack drove a man up a birch tree, and when hunters later shot the pack they discovered an interesting detail. It turned out that the pack leader was an ordinary mongrel.

It has long been a well-known fact that the wolf population grows rapidly during times of war and ruin. But there is nothing mystical about this phenomenon. It is just that when animal instincts begin to dominate in the human world, we have more important things to worry about than wolves.

Photographs by Andrei Gilbert. Translated by Joanna Dobson